Supporting Evidence in Questions for Reading Assessments

My teaching career started in 2014 as a special education teacher for middle schoolers (~ages 12-15). Since then, I’ve moved on to teaching history at the high school level with some much older students. I was recently thinking back about these two seemingly disparate jobs–just kind of my educational journey in general–and I stumbled across something that I feel like both of these jobs shared in common: the need for students to be able to read and use evidence.

Let me be very clear that this is NOT a blog advocating for more reading assessments. I think I can vouch pretty safely that most teachers feel like there’s already an overwhelming amount of quizzing and standardized tests that they and their students have to deal with.

Instead, I want to focus on how we can improve the evidence-rich reading assessments and practices we’ve already got going on.

Think of testing like recycling. We don’t need a bigger landfill. We need a better way to reuse and revamp the tests we already have.

So, my purpose here is threefold:

1. Explain the recent phenomenon with non-fiction texts, which lend themselves to supporting evidence questions.

2. Discover how to write better kinds of these questions.

3. Describe some techniques that can help develop learners’ ability to find/use supporting evidence, after you’ve assessed them.

Let’s get to it!

If you’re not familiar with this kind of question type, supporting-evidence questions especially become much more prevalent–at least in the United States –since 2010, when the Common Core (a new sort of national standards) came into being.

For our purposes here, we want to focus on the fact that Common Core essentially attempted to equalize students’ exposure to fiction and non-fiction texts (Coleman & Pimental, 2012), which in turn focused educators towards parts of reading comprehension like evidence and supporting details.

First, we should address the obvious question: “do non-fiction texts and supporting detail questions matter?” The answer seems to be a resounding “yes” from researchers. Students who interact with informational and non-fiction texts:

– Develop background knowledge, which affects up to 1/3rd of the variance in students’ achievement (Marzano, 2000).

– Are more likely to earn higher grades in certain college courses (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010).

– Have increased motivation to read when they can examine areas of personal interest (Caswell & Duke, 1998).

If our students should be reading non-fiction and informational texts, being able to assess their skills to do so is a logical next step. However, we need to be really careful with the style and demands that our questions make of students. If the questions are too easy, we’ve wasted our time and our students’ effort. If they’re too hard, and we’ve only managed to measure students’ frustration.

To help give some context and examples of how to write better kinds of questions, I’ll be continually referring to one of my own formative assessments –it’s available here.

Assuming you’ve got a text ready to go, let’s quickly define the different kinds of supporting-evidence questions you can make. McKenna & Stahl (2015) identify three different ones, and each is progressively more difficult.

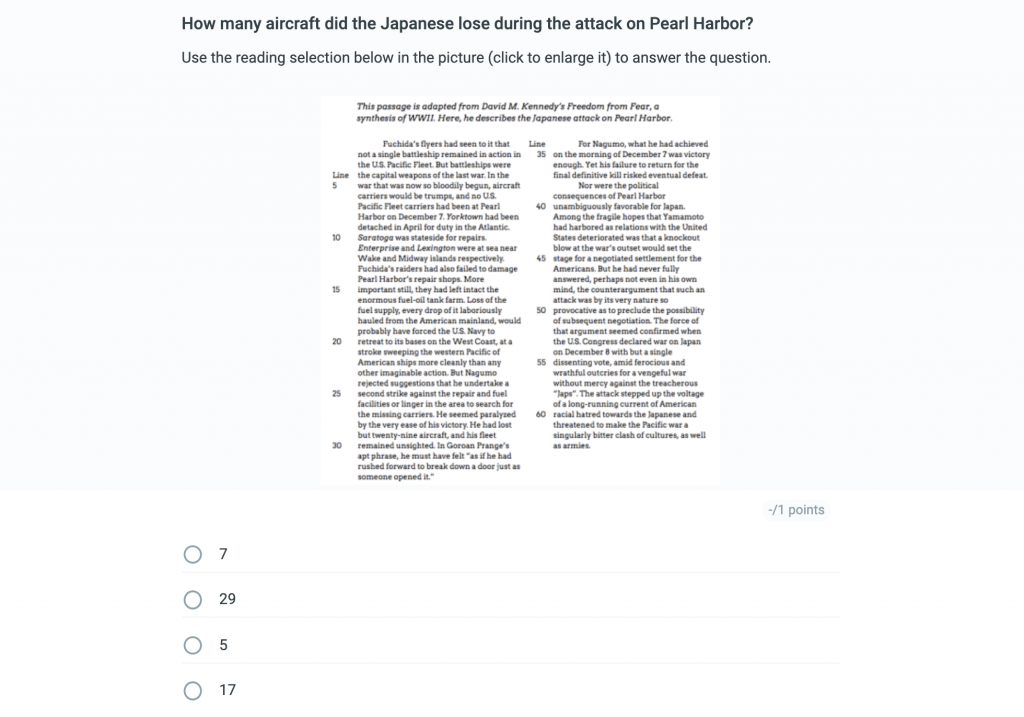

1. Literal questions demand the student to utilize information directly stated in the text. These questions tend to be pretty straightforward and only require superficial understanding.

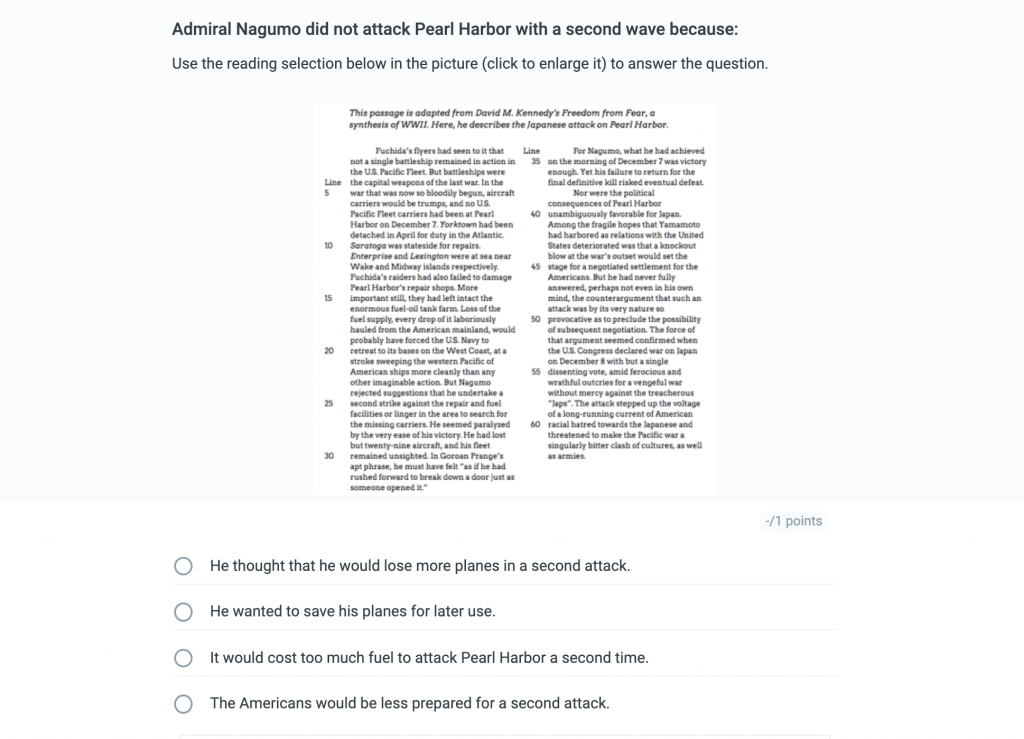

2. Inferential questions require reading between the lines–some have factual answers by “connecting the dots”, others are more speculative, such as with prediction-making. These questions are a little bit tougher because they ask students to go beyond what’s immediately available to them in a text and cite implied evidence or conclusions.

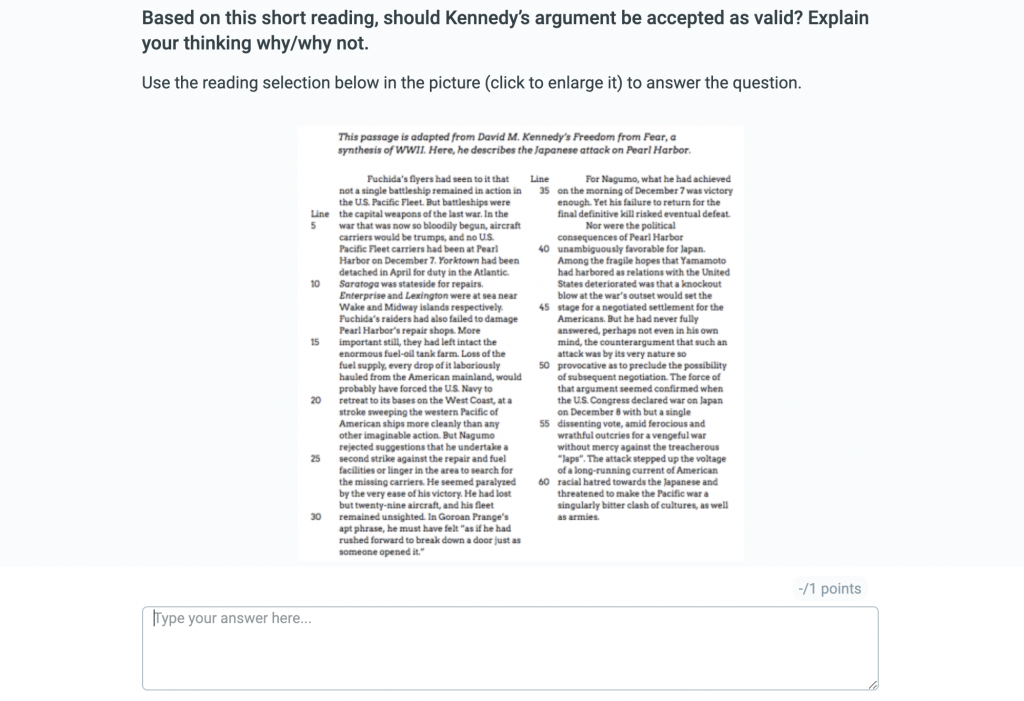

3. Critical questions want testers to form judgments and values about a selection. These questions require a lot of time and can be hard to grade because, as McKenna & Stahl explain, “they are evaluations arrived at on the basis of an individuals’ value system” (2015).

Coming up with appropriate supporting evidence questions and answers for students is both an art and a science. On the one hand, it takes some creativity to assemble questions and answers, but they have to be designed within–or just slightly beyond–the abilities of your students. Think of it like an architect and engineer working together: the architect asks “what’s possible?”, but the engineer asks “how can/should we make that work?”.

The construction metaphor is actually really useful for describing the rigorousness of your supporting-evidence questions. Whether they’re literal, inferential, or critical, consider the cognitive “loads” of your questions carefully. Sometimes, questions put hidden “stresses” of our students. For instance:

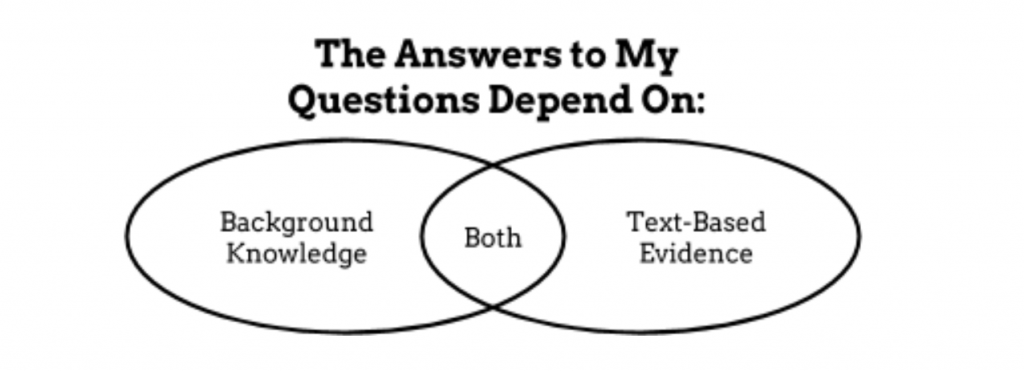

1. Sources of Supporting Evidence

Do your questions depend on students’ background knowledge or on knowledge they get from reading the text? Does it depend on both?

For instance, check out this question:

Many of my students had studied WWII before taking my class and knew beforehand that America’s aircraft carriers were not sunk at Pearl Harbor. Thus, this question was easier for them because they could automatically eliminate answer option “D”.

2. Familiar Vocabulary

If a student gets a question wrong, it may not be a result of them not knowing how to utilize evidence–it could be due to their command of vocabulary. In the example below, a student might choose “defiant” instead of “oppositional”, even though they understand the meaning of the passage. Oppositional may simply be a word that’s not yet in their lexicon.

When in doubt, my singular recommendation for making a good supporting-evidence assessment is McKenna’s and Stahl’s “K.I.S.S.”. Keep It Simple, Stupid. Don’t let the text of the questions and answers get in the way of your students’ success.

Once you’ve made your supporting-evidence assessment and given it to students, the next step is doing something about the results, especially for students who struggled with your test or quiz. As a sort of learning “engineer”–the metaphor won’t go away!!–how can you structure (oh goodness)–your students to do better?

I’m going to give you my favorite strategies from the go-to-text for troubleshooting educators: McCarney et. al’s Pre-Referral Intervention Manual (2006). They’re applicable for any student at any age.

| Have your students pretend to be detectives and play a game called “Prove It”. After reading a selection, identify the main idea . Then, the students must “prove it” by retelling the supporting details that were in the text. | Have your students partner up and model for one another how to find supporting details. |

| Read a text with students three times. First, give students time to read a selection once for fluency (to read through it). Second, have them read for comprehension (main idea). Third, to find supporting details. | Use texts for your assessments that are of high interest to the students in your classroom. You can even substitute in their first names or known locations and make the text about them! |

| Reduce the amount of information that the student has to “piece through”. For instance, after reading a passage, literally eliminate sentences or paragraphs that are not relevant to finding supporting details. | Using a picture of a house (oh no! not another construction metaphor). Have students write the main idea as the “roof” and supporting details as “walls”. You can even customize the houses based on the text you’re using! |

Until next time, happy assessing!

Further Sources

Goodwin, B., & Miller, K. “Research Says / Nonfiction Reading Promotes Student Success”. Educational Leadership. (Dec. 2012-Jan. 2013) Vol. 70, No 4., p. 80-82.

Common Core: Now What?

Gewertz, C. (2012). Districts gird for added use of nonfiction. Education Week, 31(12), pp. 1, 14.

This is a guest post written by Nate Ridgway, a tech-loving history teacher in Indianapolis, Indiana. He specializes in lesson design and differentiation, and also is licensed in Special Education Mild Interventions. He’s taught in both middle school and high school settings, but currently is enjoying teaching World History & Dual Credit U.S. History. He currently is working on finishing a Masters degree in History at the University of Indianapolis and serves on Classtime’s Pedagogical Advisory Board.

This is a guest post written by Nate Ridgway, a tech-loving history teacher in Indianapolis, Indiana. He specializes in lesson design and differentiation, and also is licensed in Special Education Mild Interventions. He’s taught in both middle school and high school settings, but currently is enjoying teaching World History & Dual Credit U.S. History. He currently is working on finishing a Masters degree in History at the University of Indianapolis and serves on Classtime’s Pedagogical Advisory Board.